BARCELONA, ANDALUSIA, MADRID, LISBON – 05 / 2018

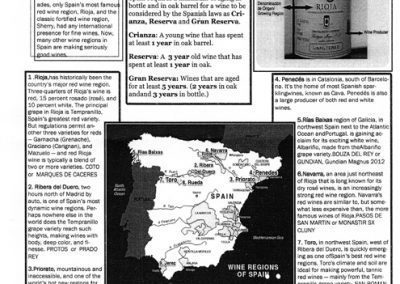

DAY 1: Fri May 18 / Sat May 19, 2018 - Arrive Barcelona

2. Flight and arrival notes:

Smooth, comfortable flight. Even managed to sleep for a few hours. Frankfurt connection to Barcelona was stressful. Long security line and extra-thorough bag check. I needed every minute of the 1.5-hour layover to make my connecting flight. Then I had to check my carry-on bag at the gate.

At the Barcelona airport, in the enormous line-up of sign-holders at the exit gate, I found the Tauck sign-holder after three passes. We then connected with the other Tauck arrivees, the Winer family from Los Angeles, and drove with them into the city arriving at our hotel, Le Meridien Barcelona more or less on time, about 1 pm. I checked in right away, unpacked, and had a nap while waiting for Holly to arrive, which she did more or less on time as well.

After Holly settled in, we went for a before-dinner stretch along Las Ramblas. Fodor’s writes that Somerset Maugham described Las Ramblas as “the most beautiful street in the world.” It is five streets in one —hence both the plural and singular versions: Las Ramblas and La Rambla, although the singular version is further defined by the unique feature of that particular part of the street: La Ramble de Canaletes, La Rambla dels Estudis, La Rambla de les Flors, La Rambla dels Caputxins, and La Rambla de Santa Monica. The word rambla comes from the Arabic word raml meaning riverbed. The original site was a small river that ran outside Barcelona’s mediaeval city wall. In the late 1700s, it was filled in becoming the newest and most fashionable street for the mansions of cash-rich Catalans. Since 1994, Las Ramblas has come to include the Rambla del Mar, a walkway from the Passeig de Colom to the Maremagnum entertainment complex.

Our walk included a too-brief visit to the Mercat de Sant Josep de la Boqueria, often simply referred to as La Boqueria, the large public market that is one of the city’s major tourist attractions. It was Saturday night and, alas, the last time we were to find the market open during our stay in Barcelona. We took photos of the candy stands close to the entrance, and subsequently regretted not purchasing some of these fantastic, creative confections.

3. Dinner with Holly at the CentOnze, the hotel’s restaurant fronting onto Las Ramblas. (The hotel’s address is Ramblas, 111, 08002 Barcelona) A great evening despite both of us being very tired. So happy to be re-united and to hear face-to-face about her new life in Mexico City.

DAY 2: Sun May 20, 2018 - Experience Barcelona

1. With an eye to our 12-noon guided tour of Park Guell, we ventured no farther than our lobby for breakfast—coffee and a pastry in the Longitude Bar 02º 10′ 10:00-ish. The Park is a 15-minute uphill walk from the closest metro station. Timing concerns more than this ‘challenge’ were why we decided to taxi, which took about 20 minutes, plus gave us a brief look at the northern parts of the city. We arrived at the already busy entrance to the Park in lots of time for our own walkabout in the areas outside the ‘Monumental Zone’ accessible only by ticket.

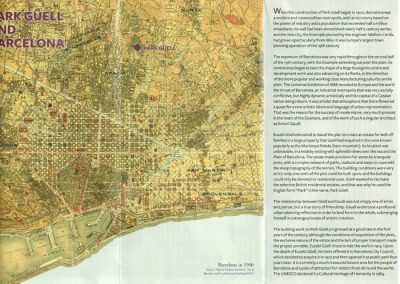

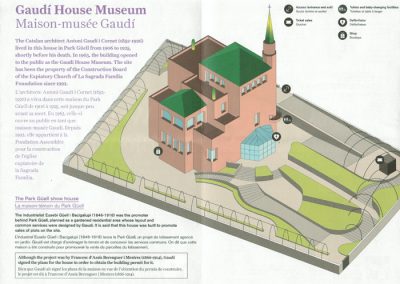

The construction of Park Guell began in 1900 when Barcelona had already burst through its old city walls and expanded into the tightly-grided area known as the Eixample, the largest town planning expansion of the 19th Century. The park is named after its developer, Eusebi Guell, a wealthy and influential Catalonian entrepreneur who envisioned an upscale subdivision north of the expanded city in a rural setting that just happened to have magnificent views overlooking Barcelona, to escape what he regarded as the negative aspects of life in the city core—the noise, the lack of fresh air, the crime. The development used the English term ‘Park’ because the template he had in mind included residential estates and parks he had visited in England. Gaudi, who had designed Guell’s townhouse, Palau Guell, was part of the project from the start. Ultimately, when the project failed to secure any buyers, Gaudi moved himself and his small family consisting of his father and niece into the one model house built, apart from the house built for Guell, and the one existing house on the property purchased by Guell’s lawyer. From this house, now Casa Museu Gaudi, Gaudi could see the Sagrada Familia site, his life-long project.

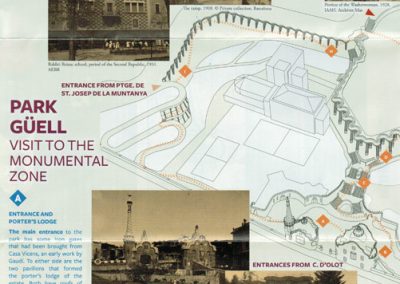

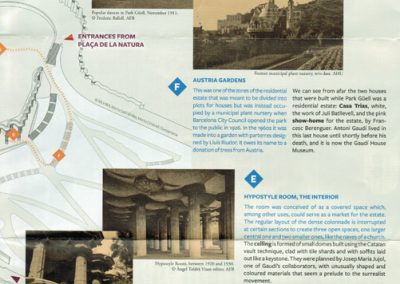

Our guide was excellent: a confident, witty, young man well used to herding groups of tourists of all types and origins. We were confused, though, by his instructions regarding areas we could continue to explore and areas outside the Monumental Zone, which, once exited, could not be re-visited. We missed seeing the shop in the Porter’s Lodge and climbing the stairs up to the Hypostyle Room to get a closer look at the trencadis salamander or dragon, a signature feature of the park. The tour ended with sitting on the undulating bench around the edge of the Nature Theatre—surprisingly comfortable for concrete! Reconstruction/renovation work was underway on parts of the roof—always the way with major tourist attractions. Maybe they do this to ensure tourists will have to return in the hope of seeing the attraction one day without scaffolding or hoardings.

2. We bought a separate ticket to visit the Casa Museu Gaudi, the house Gaudi lived in from 1906 to 1925, the year before he died. In 1963, it opened as a public museum outside the ‘Monumental Zone’ of the Park Guell. As the brochure says: “Today the house museum illustrates the architect’s private life and religious devotion through personal effects, recreations of some of the rooms, and an audiovisual.” We both found it well worth visiting especially for the chance to see his very spare bedroom and room for private devotions. We learned that Gaudi had three main priorities and interests in his life: nature, architecture, and religion. On the exterior of Casa Gaudi beside the front door was a small statue of Saint Anthony. Gaudi saluted this statue daily as he came and went. While his niece did most of the housekeeping chores, he prepared his own vegetarian food. The house had large windows that filled it with light. The room sizes were comfortable—not too big, and not too small. Indeed, it was lovely and charming, with beautiful aspects on the surrounding gardens, also well designed and complementary to the house. The furniture on display wasn’t much to our taste—a bit tortured in shape although well crafted using high quality materials. It appeared to be strong and durable.

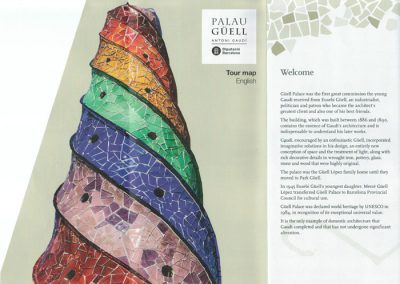

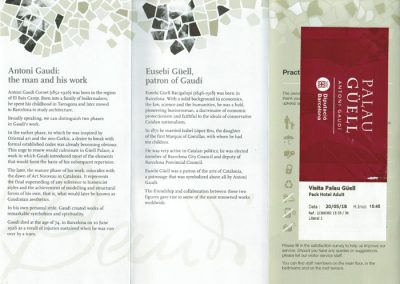

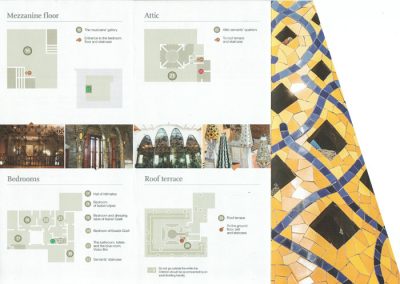

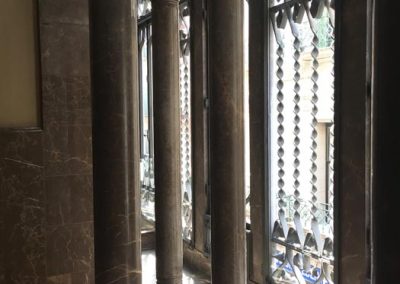

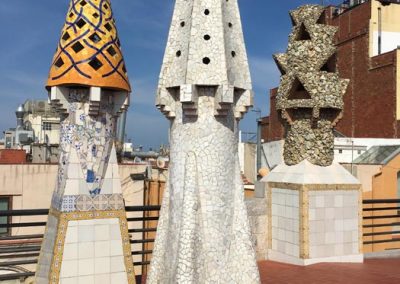

3. Taxied back to the hotel for a quick coffee and snack again at the Longitude Bar 02º 10′ and then used a complementary pass (one free ticket at least!) to visit the Palau Guell, located a few blocks south of our hotel at Nou de las Ramblas, 3-5. This made for an all-Gaudi-day, but, since the more we saw the more we liked, we were happy. This museum was founded in 1945 when Guell’s youngest daughter, Merce Guell Lopez transferred her family home to the Barcelona Provincial Council for cultural use. It was Gaudi’s first commission from Eusebi Guell, built between 1886 and 1890 to house the Guell family: Eusebi, his wife Isabel Lopez Bru, the daughter of the first Marquis of Comillas, and their ten children. It was not as much to our liking—dark, a warren of overheight rooms circling around a high central hall with a huge organ designed for formal entertaining, albeit exquisitely decorated in wrought iron, pottery, glass, stone, and wood—a display of extraordinary craftsmanship in all of these various decorative and functional materials. The roof terrace was the highlight for us—perhaps the first roof deck in Barcelona? Of course, once you focus on chimneys ancient and more contemporaneous with Gaudi’s creation, you start to see many possible influences. But, what with the trencadis cladding, the oversizing, the shape variations, and the multiplicity ‘magical’ seems the best descriptor. I wonder how many times the children escaped to the roof terrace to play. I’m guessing it was their favourite spot in the whole house despite there being ample games rooms and other areas for entertainment.

From Antoni Gaudi, Rainer Zerbst, Taschen, 2002: “The roof was always an important element for Gaudi, and he gave his fertile imagination free rein in designing it. And it never bothered him that the forms, many of which are quite bizarre, could usually not be seen from the street. The roof is topped by a small cupola which rises above the hall in the centre and tapers off into a pointed tower, lending the building a peculiarly religious air. Yet the tower clashes completely with the rest of the building—even in its colour; it is simply stuck on the top. It is surrounded by 18 surrealistic “sculptures” which remind one of the legs of the dressing table. These are early examples of the little turrets Gaudi was later to sublimate in the form of the mitre-like spires of the Sagrada Familia: small, often twisted formations with additional ornamental points and corners, which look like sheer playfulness and yet, as so often in Gaudi’s works serve highly practical purposes—they are both chimney decorations and ventilation ducts. Gaudi detracted from the ordinary function of these elements by adding the lavish ornamentation of colourful tiles.”

4. Home to get ready for Tauck’s ‘Welcome Reception’ and the first dinner with our fellow travellers, which started at 6:15 pm and ended not late. We dined in the CentOnze restaurant at a large table with the Winers, the Harris family, and two sisters-in-law we took to calling the ‘Exotic Omas’. On both of our Tauck Tours, the people we dined with on the first night were the people we tended to remain most closely connected with throughout the whole of the trip. Can’t say enough good things about Tauck—their info sheets, for example, their ‘app’, and our personable, smart, organized, fun tour guide Alicia. Tauck is masterful at making everyone feel welcomed, included, and ‘on board’ with the myriad details of timing, location, ticketing, that must be attended to by everyone for the whole effort to proceed without a hitch. Which it did!

DAY 3: Mon May 21, 2018 - Experience Barcelona

1. Walking tour of Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter

This first full day of our Tauck Tour began early with breakfast in the CentOnze restaurant in our hotel, followed by a meeting in the hotel lobby at 8:15 am to divide into two groups, meet our group’s guide, and begin our walking tour through the Gothic quarter across the street from our hotel, i.e., east of La Rambla.

As I attempt to retrace this tour with the help of my photos, my recollections of our route and what buildings we saw are vague. Maybe it was too early, maybe it was the maze-like narrow streets, maybe all the names of the government buildings were too complicated, maybe because there was no sign of Gaudi! Or maybe I was just distracted by all the signs of design-y Barcelona today, the great graffiti and shop windows.

My photos begin in the Placa del Pi where we focused first on the sgraffito work on the buildings surrounding the square and its signature pine tree. Sgraffito is a decorative technique in which a top layer of coloured plaster is scratched off to reveal the usually lighter colour beneath. It was widely used in 18th century Barcelona. Once single-owner ‘palaces’, today these buildings are high-end apartments. The square hosts a weekly farmers’ market. The giant rose window of the Esglesia de Santa Maria del Pi that looms over the square was covered for renovation work.

From here we walked through narrow shop-filled streets. My attention was on the shops and the general look of these lane-scapes rather than the Roman walls etc. we were being told about. Hence the photos of shop windows and their graffiti covered protective gates. Fantastic graffiti everywhere!

Monday has to be one of the quieter days in bustling Barcelona simply because many of the main tourist attractions are closed that day. So, perhaps thanks to this, but also to our early start, this walking tour was especially suited to moseying along and just soaking in what caught your eye and not necessarily what you had paid to be told about. The weather was perfect; the slight morning chill a wake-up. The streets were quiet; our guide, in the spirit of the moment, whispered into his microphone. The squares were empty; the narrow streets almost empty. I must remember how nice it is to start exploring these jam-packed cities of Europe in the early morning. Once the hustle starts, it accelerates rapidly.

2. The Picasso Mural on The College of Architects of Cataloni

Eventually, we arrived at the ‘squares’ in front of the Cathedral, the Placa de la Seu and/or the Placa Nova. The College of Architects of Catalonia which fronts onto the Placa Nova is identifiable by its unique modern style—unique that is for this area of town — and the simple line drawing mural by Picasso that wraps around the exterior concrete cladding over the first floor. Fodor’s says Picasso designed it in the 1950s when he was “in self-exile from Spain for his (anti-Franco) political beliefs.”

From online: Entry speech of the Illustrious Elect Academic. Mr. Xavier Busquets i Sindreu

Read in the Lecture Hall of the Academy on the 9th December 1987, Report dated 18-07-2012

In May 1955, the Official College of Architects of Catalonia and the Balearic Islands inaugurated its new headquarters in the Plaça Nova of Barcelona, in front of the Cathedral. The building was decorated with some friezes by Picasso, produced by the Nordic artist Carl Nesjar. The Architects’ College (COAC) is celebrating its 50th anniversary and from the museum we would like to celebrate this milestone by remembering the words of Mr. Xavier Busquets i Sindreu, the architectural director of project, in which he explains, in a very personal and detailed way, the whole process, from the idea to the production of these friezes.

Front and right side facades of the building of the College of Architects of Catalonia

“I was very lucky to win the two contests and to be charged with carrying out the project and to take on the management of the works. As soon as the Barcelona public learned about the draft project, a considerable controversy began. The current style of the building projected and its location, right in front of the solid Roman Wall, of the Bishop’s Palace, the House of the Archdeacon, and of the Cathedral, lead to extensive discussion. Some spoke of the breaking of the architectural harmony of the setting. Others were of the opinion that the contrast between the building and its surroundings gave mutual value to them […]. The criticisms and the debates were heated, and, all in all, achieved a very agreeable result: that of stirring up the interest of the public in architecture. […]

With regard to the building, the blind wall of the first floor, which surrounded the lecture hall and the foyer, was a problem that especially worried me, given that it constituted a transition from one horizontal element to another vertical element. The initial idea had been to resolve this with a covering of stoneware ceramic charged to Antoni Cumella. Two facts contributed to modifying this first idea. Some years before, finding myself in Cannes I had met Pablo Picasso in person. […] His interest in our city was immediately very clear to me. Practically the first question he asked me was: “What are they doing in Barcelona?” And he listened to my explanations with an attention and friendliness that in no moment were refuted. […] It was an unforgettable afternoon for me. He had received me in a room organised on the basis of a magnificent mess. […] Of that first visit to Picasso, lost in time, I kept the inalterable impression of honest hands and of eyes of an implacable curiosity, corrected by experience. […] In October 1958, on a trip to Paris related to the project of the College, I also visited the UNESCO, where I saw a mural of Miró done with the collaboration of Llorens Artigas. This mural and the memory of my visit to Picasso provoked the idea of a possible collaboration between Picasso and Cumella for the building of the College. The enormous prestige of Picasso, his unarguable mastery, and his very close link of so many years in Barcelona and Catalonia were decisive factors for a certain success. […]

RIGHT: Front and right side facades of the building of the College of Architects of Catalonia

RIGHT: Front and right side facades of the building of the College of Architects of Catalonia

Thus I went to visit Picasso again. I did so, provided with the plans and perspectives of the building and collections of photographs that reproduced its location and its future aspect. As is natural, at no stage had I proposed a specific topic to Picasso for the decoration of the murals. […] As has already been said, my first idea was that of a collaboration of the potter Cumella with Picasso. But about this, with the interest for new ways of expression that always characterised him, he spoke to me of a new procedure with which he had reproduced some of his drawings from the Grimaldi d’Antibes Museum on the building of the Norwegian government in Oslo.

Carl Nesjar, who knew Picasso and the new technique of sandblasting had already managed to take on the responsibility for the work and moved to Barcelona. I remember him as huge Nordic man, tall and robust, bearded. […] We had therefore decided the materials with which we would work. But we still lacked the original drawings. […] With the intention that he wouldn’t feel excessively pressurised, I kept him up-to-date with everything. I visited him every month and spoke to him on the phone weekly. […] Meanwhile the works of the building advanced, and soon we would reach the stage of the finishing works. Everything was ready for the murals to begin. One day, when saying goodbye to Picasso and Jacqueline at “La Californie” (Picasso’s villa at Cannes, France in which he lived from 1955 to 1961) I dared to say to him that we couldn’t delay it any more. “Pray to Our Father that I do it”, Picasso responded to me. Just a few days later, on the 18th October 1960 at eleven o’clock at night, he telephoned me to say that the drawings were ready. […]

On showing me the drawings, Picasso mentioned the willingness for synthesis and the effort of simplicity that they represented. “This – he concluded literally – I wouldn’t have been able to do before.” And, effectively, the drawings had much more wisdom and depth than they seemed to have at first sight.

The moment had therefore arrived to begin the definitive works. […] The reproduction of the drawings was done in two phases. It was first necessary to reproduce fragments of the originals in paper, enlarging them until the definitive size was obtained. The drawings were photographed on slides. And these were projected on paper, and Carl Nesjar retraced the drawing with a paintbrush. So as to do the enlargement to the size that the friezes presented it was necessary to project the slides from more than 10 metres away. […] Once the drawing on paper was passed to the natural scale, the paint strokes were followed by perforating them with a punch.

Left side of the building facade

Left side of the building facade

The second phase of the reproduction took place in the College itself. The painted papers were fixed on the recently unpacked concrete panels. Carl Nesjar, with a small canvas bag full of graphite dust followed and hit the perforated tracing of the drawing. The graphite passed through the holes of the paper and marked the lines on the concrete. Once the paper was taken off, looking at a photograph of the originals, Nesjar went over the lines with a crayon and marked with arrows the direction which the sand should be blasted, with the aim of exactly reproducing the different intensities of the lines of the drawing of Picasso. Finally, the time arrived for blasting the sand following the marks and uncovering the black stones inside the concrete. […] The sand and mortar created a formidable cloud of dust. To avoid this as far as possible, large fans were used to project the dust into a curtain soaked in water. […] The process required the removal of the mortar with great care, repeatedly consulting the photographs of the originals, so as not to make the lines too thick.

Having spread the word that the decoration of the exterior panels of the College was produced from original drawings by Picasso, there were various artists who would have wanted to contribute their knowledge to the decoration of the interiors. For the two wall panels of the foyer, the prolongation of the lecture hall, I had thought of Joan Miró. I commented this possibility to Picasso. The reaction was fast and cutting: “I’ll do them for you, the ones of Miró!” he said to me. He did them with surprising speed.”

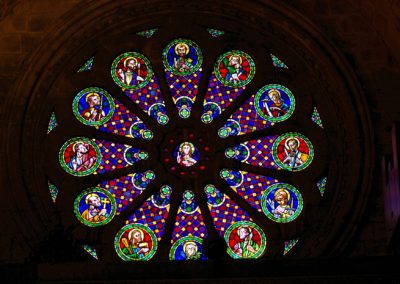

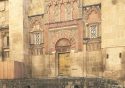

3. Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia

Many of the buildings on these squares are noteworthy and we were told about their origins and current restoration and usage. …And then we went into the cathedral named after Saint Eulalia, one of Barcelona’s patron saints; its official name — Catedral de la Santa Creu i Santa Eulalia, Catalan for “Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia”. The commonly used name La Seu refers to the status of the church as the seat of the diocese.

It is a celebrated example of Catalan Gothic architecture with a long history, given its prime location on a hill:

- The first structure on the site was a Roman temple

- It was followed by a paleo-Christian basilica constructed in the 4th century and ennobled by subsequent bishops over seven centuries.

- …Which was then converted to use as a mosque under the Arab occupation beginning in 711 AD.

- Construction of the present-day cathedral began under the reign of Jaume II (James II) at the end of the 13th Century. The bishops ordered a single nave, 28 side chapels, and an apse with an ambulatory behind a high altar. Four different architects worked on it over the next 150 years.

- Work was completed in the mid-15th century under the mandate of Bishop Francisco Clemente Sapera and the rule of King Alfonso V of Aragon, except …

- The front facing façade and the spires were embellished in 1913 in a design based on the plain brick and stone front in place since the 15th century. At the end of the 19th century, the Barcelona industrialist, Manuel Girona Agrafel had offered to undertake the work on the façade and on the two side towers, in keeping with the plans drawn up by the architect Josep O. Mestres and inspired by the initial 15th-century project. Mr Girona’s children finalized their father’s work in 1913 on completion of the cimborio — a raised structure like a dome or a cupola; specifically a lantern usually octagonal in plan built over the crossing of a Gothic cathedral.

- The total area occupied by the building is 3,600 square meters. Basic dimensions: 90 metres (300 ft) in length and 40 metres (130 ft) in width. The total height of the two towers is 53 metres (174 ft).

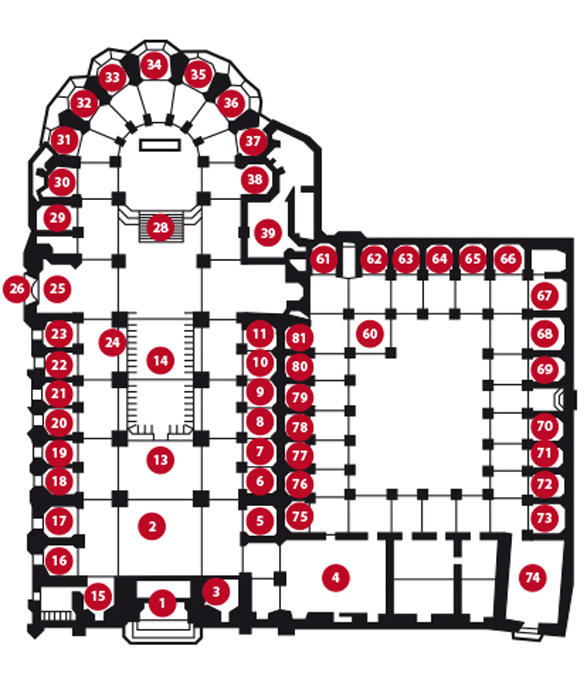

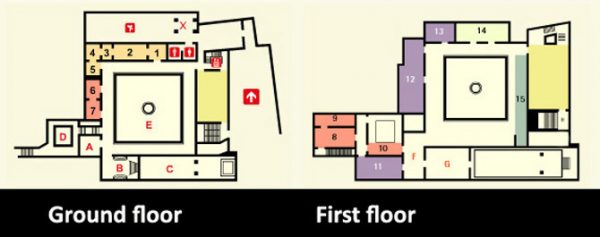

The diagram below is from the Cathedral’s website, catedralbcn.org. The red dot numbers—81 in total—show the locations of the main ‘advocations’ represented in the Cathedral. There are more than 140. The Virgin Mary is most frequently represented, followed by Saint Eulalia and the Archangels Saint Michael and Saint Gabriel. Among the most recently added are a monument to Saint Josep Manyanet on the altar to the Virgin of Pilar, a sculpture of beatus Pere Tarrés, a sculpture of beatus Josep Tous, and a group of sculptures dedicated to the 146 pious victims of religious persecution from 1936-1939 in different chapels of the Cloister.

Cleaning and restoration of the cathedral was carried out from 1968-72.

The size of the space, the intricacy of the decoration of the side chapels—lots of gold! —the size of the organ, and the historical importance of the central choir were impressive. Next time I visit I want to see it at night. These images are dazzling revelations of the delicacy of the exterior decoration.

A few of the noteworthy features:

(1) Saint Eulalia, located in Chapel 28, Sepulcher Crypt, retrochoir (c. 290–12 February 303), (from Wikipedia) co-patron saint of Barcelona—with Saint George, was a 13-year-old Roman Christian virgin who suffered martyrdom in Barcelona during the persecution of Christians in the reign of emperor Diocletian (although the Sequence of Saint Eulalia mentions the “pagan king” Maximian). There is some dispute as to whether she is the same person as Saint Eulalia of Mérida, whose story is similar. For refusing to recant her Christianity, the Romans, before decapitating her, subjected Eulalia to thirteen tortures including:

- Putting her in a barrel with knives (or glass) stuck through its sides and rolling the barrel down a street —according to tradition, Baixada de Santa Eulalia “Saint Eulalia’s descent”

- Cutting off her breasts

- Crucifying her on an X-shaped cross with which she is often depicted

Following Eulalia’s decapitation, a dove is said to have flown out of her neck. Her body was originally interred in the church of Santa Maria de les Arenes (St. Mary of the Sands; now Santa Maria del Mar, St. Mary of the Sea). In 713, during the Moorish invasion, it was hidden and only recovered in 878. Then, in 1339, it was relocated to an alabaster sarcophagus in the crypt of the newly built Cathedral. This crypt is visible directly below the main altar. There are railings around the crypt entrance and steps on either side of it. Along with the location of the choir stalls in the centre of the nave, this layout seems unique, and it would seem to disconnect the congregation from the services of worship. The soaring height of the interior space, the stained glass windows, and the side chapels captured my attention more so than did the altar and the front of the church.

Eulalia is commemorated with statues and street names throughout Barcelona. The festival of Saint Eulalia is held in Barcelona during the week of her feast day on February 12.

(2) The central choir (No. 14 on the diagram) has carved and painted choir stalls. Under the misericordias (seats) are reliefs of hunting scenes and sports including golf. (See my photo of the carved golf relief.) The decorative painting includes coats of arms for the knights of the chapter of the Barcelona Order of the Golden Fleece, mostly European monarchs and nobles who, in 1519, attended an assembly in the Cathedral organized by Charles V.

The Order of the Golden Fleece is a Roman Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by the Burgundian duke Philip the Good in 1430, to celebrate his marriage to the Portuguese princess Isabella. Duke Philip III proclaimed he founded the Order “for the reverence of God and the maintenance of our Christian Faith, and to honour and exalt the noble order of knighthood, and also …to do honour to old knights; …so that those who are at present still capable and strong of body and do each day the deeds pertaining to chivalry shall have cause to continue from good to better; and … so that those knights and gentlemen who shall see worn the order … should honour those who wear it, and be encouraged to employ themselves in noble deeds…”.

To accusations of prideful pomp against the Order, the Burgundian court poet Michault Taillevent, asserted it was instituted:

Not for amusement nor for recreation

But for the purpose that praise shall be given to God,

In the very first place,

And to the good, glory and high renown.

Historically, The Order of the Golden Fleece conferred privileges unusual to any order of knighthood. The sovereign undertook to consult the Order before going to war. All disputes between the knights were to be settled by the Order. At each assembly of the Order (or chapter) the deeds of each knight were reviewed, and punishments and admonitions were dealt out to offenders. The sovereign was expressly subject to this review as well. The knights could claim as of right to be tried by their fellows on charges of rebellion, heresy, and treason, and Charles V conferred on the Order exclusive jurisdiction over all crimes committed by the knights. The arrest of an offender had to be by warrant signed by at least six knights, and during the process of charge and trial he remained not in prison but in the gentle custody of his fellow knights. The Order, conceived in an ecclesiastical spirit in which mass and obsequies were prominent and the knights were seated in choir stalls like canons, was explicitly denied to heretics, and so became an exclusively Catholic honour during the Reformation.

Since its establishment, the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece has had only 1,200 recipients making it the most prestigious and exclusive order of chivalry in the world, both historically and contemporaneously. Unique amongst all distinctions, it is only granted for life and must be returned to the Spanish Monarch upon the death of the recipient. Each collar is fully coated in gold, and is estimated to be worth around $60,000 USD, making it the most expensive chivalrous order. Two branches of the Order exist today, the Spanish and the Austrian Fleece. The current grand masters are Felipe VI, King of Spain, and Karl von Habsburg, grandson of Emperor Charles I of Austria, respectively.

Charles V ruled the lands of the former Duchy of Burgundy from 1506, the Spanish Empire (as Charles I) from 1516, and the Holy Roman Empire from 1519. His domains spanned nearly 1.5 million square miles, including extensive territories in western, central, and southern Europe, and the Spanish viceroyalties in the Americas and Asia. Thus he was the first sovereign whose empire could be and was described as one on which ‘the sun never sets’.

In more detail: Charles was the heir of three of Europe’s leading dynasties: the Houses of Valois-Burgundy (through his paternal grandmother), Habsburg, and Trastámara (his maternal grandparents were the Catholic Monarchs of Spain). Charles inherited the Netherlands and the County of Burgundy as heir of the House of Valois-Burgundy. As a Habsburg, he inherited Austria and other lands in central Europe. He was also elected to succeed his grandfather, Maximilian I, as Holy Roman Emperor, a title held by the Habsburgs since 1452. From the Spanish House of Trastámara, he inherited (from his maternal grandmother Isabella I of Castile) the Crown of Castile, which was developing a nascent empire in the Americas and Asia, and (from his maternal grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon) the Crown of Aragon, which included a Mediterranean empire extending to Southern Italy. Charles was the first king to rule Castile and Aragon simultaneously in his own right (as a unified Spain), and as a result he is often referred to as the first king of Spain. The personal union under Charles of the Holy Roman Empire with the Spanish Empire was the closest Europe would come to a universal monarchy since the death of Louis the Pious (778–840), the son of Charlemagne.

On 10 March 1526, at the Alcázar Palace in Seville, Charles met his future wife, his first cousin Isabella of Portugal, daughter of King Manuel I of Portugal and Charles’s aunt Maria of Aragon. The marriage was a political arrangement, but at first meeting, the couple fell deeply in love, Isabella captivating the Emperor with her beauty and charm. They were married that night in the Hall of Ambassadors. Following their wedding, Charles and Isabella honeymooned at the Alhambra in Granada. Wishing to establish their residence in the Alhambra palaces, Charles began the construction of the Palace of Charles V in 1527, intending it to be their permanent residence befitting an emperor and empress but it wasn’t completed during their lifetime, and remained roofless until the late 20th century. Despite Charles’ long absences, the marriage was happy, and both partners were devoted and faithful to each other. The Empress acted as regent of Spain during her husband’s absences and proved herself a good politician and ruler. The marriage lasted for thirteen years until Isabella died following illness from her seventh pregnancy at the age of 35 on 1 May 1539. Charles was so grief-stricken that he retired to a monastery for two months to mourn in solitude. He dressed in black for the rest of his life, and, unlike most kings of the time, never remarried. In memory of Isabella, Charles commissioned the painter Titian to paint several posthumous portraits of her including Titian’s Portrait of Empress Isabel of Portugal and La Gloria. (Below is Charles and Isabella by Peter Paul Rubens)

Between 1554 and 1556, Charles V began abdicating some of his positions in favour of his son Philip, and some in favour of his brother Ferdinand. He retired to the Monastery of Yuste in Extremadura but continued to correspond widely and remain abreast of the affairs of the empire. He died on 21 September 1558, at the age of 58, holding the cross Isabella had held when she died.

(3) No. 60 on the diagram is the fountain in the center of the cloisters. This area is a garden oasis filled with orange, medlar, and palm trees, a mossy pond, and 13 white geese. The 13 geese are said to represent the purity of Santa Eulalia, and the age of her martyrdom. But they likely have even more historical importance. Egyptian tombs are decorated with images of geese; some guidebooks refer to geese in cloisters as a Roman tradition, and, according to my learned husband they make for an excellent alarm system. If they detect anything out of the ordinary, they will raise a ruckus and they can be fierce fighters. Their whiteness is in stark contrast with the fantastic dark gargoyles on the Cathedral’s exterior. The gargoyles manage to celebrate the intricate, complex beauty of the natural world even as they signify evil spirits driven out by the light of the Holy Spirit celebrated inside the building

4. The Palau Real Museum

We walked behind/beside the Cathedral and viewed but did not visit the Palau Real Major, the medieval palace used by Spanish royalty until the royal court moved to Madrid in 1561. Now it is part of a double-barrelled museum: a palace the foundations of which were discovered to overlay Barcino, a 43,000 sf Roman city, the most extensive Roman city found underground in Europe, now viewable from a network of walkways over the streets, squares, homes, shops, laundries and vats used for wine production. This is a must-see for my next visit to Barcelona

Frommer’s says the palace dates from the 10th Century when it was the palace of the counts of Barcelona before becoming the residence of the kings of Aragon. “The top step of its sweeping entrance is supposedly where King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella received Columbus after he returned from the New World.” The Palace’s chapel, the Capella de Santa Agueda is used for temporary exhibitions. The Salo del Tinell (banqueting chamber) beside the chapel features the largest stone arches erected in Europe. Another highlight is the five-storey Mirador del Rei Marti (King Martin’s Watchtower) built in 1555 as a lookout for invaders and peasant uprisings.

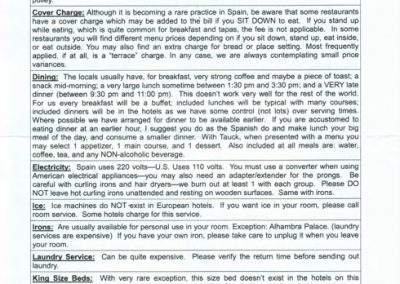

My photos also show the bronze sculpture in the square, Topos (‘Space’ in Greek) by Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002). Its dimensions are 2.10 × 2.37 × 1.70 metres. Topos was purchased by Barcelona when it was exhibited at the Joan Miró Foundation in 1986. Chillida, himself suggested the Plaça del Rei as the best site for allowing its geometrical shapes, scale, brown color, and textures to “dialogue with the sober mediaeval architecture surrounding the square, including historical buildings such as Palau Real Major, the Royal chapel of Saint Agatha and Padellàs’s House.” Topos is cast iron. Its geometrical shape reproduces a Dihedral angle, closed on two of its sides with the two ‘open sides’ facing the square. The curved forms on top of the walls evoke the letter B, for “Barcelona” and a crenelated wall, suggesting “a perfect complementarity between contemporary sculpture and medieval architecture.” (Wikipedia)

5. El Cap de Barcelona

Our walking tour of the Gothic quarter finished at the ‘Head of Barcelona’ (El Cap de Barcelona) sculpture by the US pop artist Roy Lichtenstein in the Passeig de Colom at one end of Port Vell. Commissioned by the Barcelona City Council for the 1992 Olympic Games, and made of concrete covered in ceramic tiles — trencadis, in homage to Gaudi — at 64’ 2” x 21’ 9.5” x 15’, it is un-missable. Its bright colours — white, red, blue, yellow and black, and brushstroke shapes evoking the visual language of comics are pure Lichtenstein. Consistent with a series of works in which he sculpted ‘brushstrokes’, it is a tribute to painting, to the city, and to Gaudi.

The addition of contemporary public art in historically important settings in Barcelona is significant not only because the pieces themselves are noteworthy, but also for what it says about living in a city with such a rich, multi-layered history. It honours that history but also acknowledges the spirit of modern opportunities and potentialities. This may also be the motivation behind the abundance of the generally high-keyed and high-spirited graffiti.

6. Bus tour to Montjuic

Montjuic, ‘Jewish Mountain’, so-named for the remains of a mediaeval Jewish graveyard found there, is a broad, flat-topped hill overlooking the Barcelona harbour southwest of the present day city centre. Due to this strategic location, it was the birthplace of the ancient city. Wikipedia’s summary of Montjuic’s more modern history says: “The top of the hill (a height of 184.8 m) was the site of several fortifications, the latest of which, the Castle of Montjuïc (Castell de Montjuic) remains today. This fortress dates from the 17th century with 18th-century additions. In 1842, the garrison loyal to the Madrid government shelled parts of the city. It served as a prison, often holding political prisoners until the time of General Franco. It was also the site of numerous executions. In 1897, an incident popularly known as Els processos de Montjuïc prompted the execution of anarchist supporters, which then led to a severe repression of the struggle for workers’ rights. On different occasions during the Spanish Civil War, both Nationalists and Republicans were executed there, depending on who held the site at the time. In 1940, the Catalan nationalist leader, Lluís Companys was executed there, after his extradition by the Nazis to the Franco-led government.

Once the forests were partially cleared in the 1890s, however, apart from the goings-on at the Castle, Montjuic became parkland and provided a setting dedicated to sport, to celebrating Catalan art and architecture, and to showcasing its unparalleled vistas of the city. The highlight ‘attractions’ include:

For the 1929 International Exposition:

- the grand Palau Nacional, the main site of the 1929 International Exhibition, and since 1934, home to the National Art Museum of Catalonia.

- the ornate Font Màgica fountains, and a grand staircase leading up from the foot of Montjuïc at the south end of the Avinguda de la Reina Maria Cristina, past the Font Màgica and through the Plaça del Marquès de Foronda and the Plaça de les Cascades to the Palau Nacional.

- the Estadi Olímpic (the Olympic stadium), which in 1936 was going to host an anti-fascist alternative to the 1936 Berlin Olympics until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced cancellation of this plan. The stadium served as the home for football team Espanyol, until the club left for a new stadium in Cornellà/El Prat upon its completion in 2008.

- the Poble Espanyol, a ‘Spanish village’ of different buildings built in different styles of Spanish architecture.

- Mies van der Rohe’s German national pavilion constructed at the foot of the hill, near the Plaça del Marquès de Foronda, demolished in 1930 but rebuilt in 1988.

For the 1992 Summer Olympics,

- the extensively refurbished, 65,000 seat, Olympic stadium, renamed the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys, hosting the opening and closing ceremonies and many of the athletic events

- the Anella Olímpica (the ‘Olympic Ring’) of sporting venues including the Palau Sant Jordi indoor arena, the Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya, a centre of sports science, the Piscines Bernat Picornell, and the Piscina Municipal de Montjuïc, the venues for swimming and diving events respectively

- the telecommunications tower, designed by the architect Santiago Calatrava.

For a unique way of getting around town

- the Funicular de Montjuïc, a funicular railway that operates as part of the Barcelona Metro, and then a gondola lift

- on the eastern slope the Miramar terminal of the Port Vell Aerial Tramway connecting Montjuïc with Barceloneta on the other side of Port Vell

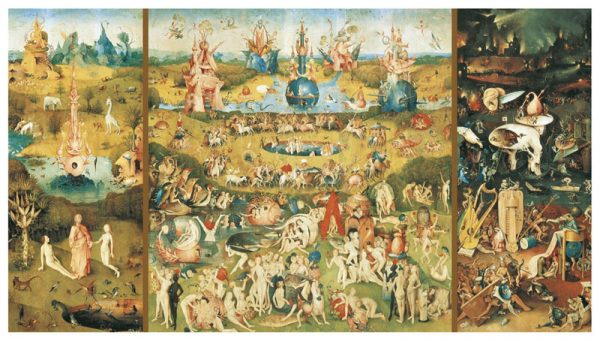

Also on Montjuïc — (From Wikipedia)

- Fundació Joan Miró, a modern art museum for the works of Joan Miró.

- Montjuïc Cemetery (Cementiri del Sud-Oest), the burial site for many influential people, including Lluís Companys and his predecessor as President of Catalonia, Francesc Macià; artist Joan Miró; dancer Carmen Amaya; and poet/priest Jacint Verdaguer. Numerous unmarked graves hold those executed in the fortress.

- The botanical gardens

- The museum of ethnology

- The Catalan museum of archaeology (housed in the 1929 exhibition’s palace of graphic arts)

- The Olympic and Sports Museum Joan Antoni Samaranch

Our bus tour was a quick circle of the west side of Montjuic with a photo stop at the Palau Nacional, at the top of the grand staircase. (See my photos) Again, this is something that, next time, I want to view by night, especially to see the lights of the magic fountain. This was my third trip up Montjuic. In our visit to Barcelona in 2015, prior to our cruise to Rome, Barney and I taxied up to tour the Fundacio Joan Miro. We also saw Montjuic from a hop-on tour bus which, as I recall, gave us more details on the various features than what we learned this trip.

Next time I want to get into the National Art Museum, the Spanish Village, some of the Olympic facilities, maybe return to the Joan Miro museum, and see the botanical gardens. And now that I have learned about the Port Vell tramway, it will be my first choice for getting there.

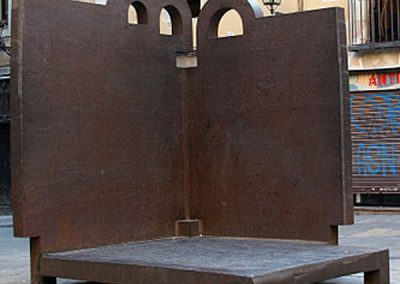

7. The Basílica i Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família — Basilica and Expiatory Church of the Holy Family

From Montjuic we bussed with our guide to Sagrada Familia. We parked about two blocks away, walked back, waited briefly for our tickets and then proceeded through security to the top of the stairs at the Nativity façade. Our tour began here. After looking at this facade, we entered, proceeded left to move clockwise around the interior to what will be the south-facing Glory façade and future main entrance, then turned and walked along the west wall. We exited via the Passion façade. At the base of the stairs to the Passion façade, we studied its detailing. We also saw the workshop and studios that have housed several of the architects including Gaudi.

Our visit was mid-day and the crowds were less than when I last visited in 2015. In that visit, we arrived about 9:30 am, and the crowds were so heavy we had trouble even making our way on the streets around the exterior. We hadn’t purchased tickets in advance so visiting inside was unthinkable.

One of the main reasons for my choosing this particular Tauck tour this year was to see the interior. Because construction has been and remains ongoing, every visit to Barcelona provides something new to see at this site. And even if the goal of completing the ‘building’ in 2026 is reached, the work on adding decorative detailing will continue. Then, inevitably, cleaning and renovating will begin. Sagrada Familia is a living, breathing monument that, among its many other accomplishments, connects the world today with the thousand-year-old Christian tradition of centuries-long church construction.

TIMELINE

1872 — After visiting the Vatican, bookseller, Josep Maria Bocabella, founder of Asociación Espiritual de Devotos de San José (Spiritual Association of Devotees of St. Joseph) forms the intention to build a church inspired by the basilica at Loreto.

1882 — Construction of Sagrada Família starts under architect Francisco de Paula del Villar. The apse crypt of the church, funded by donations, is begun 19 March 1882, on the festival of St. Joseph.

1883 March 18 — Del Villar resigns over financial squabbles, and Gaudí (aged 31) takes over as chief architect and soon begins to radically change the design.

1884 — Gaudi is appointed Architect Director. While Del Villar had envisioned a standard form church in Gothic revival style, the style of Gaudi’s creation almost defies categorization. ‘Idiosyncratic’ and ‘bizarre’ are terms often used to describe it. Wikipedia notes it is “variously likened to Spanish Late Gothic, Catalan Modernism and to Art Nouveau or Catalan Noucentisme. If Art Nouveau, the period in which Gaudi started the project, the famous architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner said, “Gaudi carried the Art Nouveau style far beyond its usual application as a surface decoration.” A ‘catechism in stone’ is another more substantive way of describing it. Gaudi was given no deadline and is quoted as saying, “My client (God) is in no hurry.”

1886 — Gaudi still believes that completion is possible within 10 years provided he is given a sum of 360,000 pesetas per year. Financial support was not guaranteed, the church having been planned as a church of atonement for the sins of the people of the city, the funding, therefore, to be by donation only.

1906 — The middle of the east-facing Nativity façade (towards Placa de Gaudi) is completed.

1914-1918 — Construction is delayed and Gaudi goes house to house asking for funding.

1925 — Gaudi moves from his house in the Park Guell to live and work in the workshop of the Sagrada Família.

1926 — Gaudi dies at age 73 after being hit by the No. 30 tram on the Gran Via. Less than a quarter of the project is complete.

1926 to 1936 — Work continues under the direction of Domènec Sugrañes until it is interrupted by the Spanish Civil War. During this war, Catalan anarchists destroy parts of the unfinished basilica, and Gaudí’s models and workshop. Present design is therefore based on reconstructed versions of the plans that were burned, as well as on modern adaptations.

1940 — The architects Francesc Quintana, Isidre Puig Boada, Lluís Bonet, and Francesc Cardoner carry on the work.

1950s — Construction resumes. Progress is intermittent.

1954 — Construction begins on the west-facing Passion façade (towards Placa de la Sagrada Familia) according to the design that Gaudi created in 1917.

1958 — Jaume Busquets produces his masterwork, the Jesus, Maria i Josep ensemble that forms the centerpiece of the Nativity Façade.

1976 — The four spires of the Passion façade are completed.

1978 — Etsuro Sotoo (nicknamed the ‘Japanese’ Gaudi) visits Barcelona, sees Sagrada Familia and ultimately, while seeking only to study with Gaudi’s design ‘disciples’ is hired to work as a sculptor/stonecutter on the Nativity façade, following, if not Gaudi’s instructions, then in the spirit of Gaudi. He came to believe that looking at Gaudi’s work was not enough, he had to look where Gaudi looked—at nature, a revelation that also motivated his conversion to Catholicism. His work includes sculpting the angels, musicians, singers, and children on the façade, and the fruit baskets that crown the pinnacles. He has also designed the doors on the facade made of polychrome aluminum and glass, decorated with plants, insects, and small animals. And he has made gargoyles for the towers of the Evangelists, currently under construction.

1980s — The current director and son of Lluís Bonet, Jordi Bonet i Armengol, introduces computers into the design and construction process helping to increase the pace of progress.

1987 — Josep Maria Subirachs commences work on the figures for the Passion Façade. Unlike Sotoo, Subirachs makes few if any concessions to Gaudi’s ‘style’ and is highly criticized for this approach.

2000 — Central nave vaulting is completed.

2002 — Construction begins on the south facing Glory façade, which will be the principal façade providing access to the central nave and, hence, the largest and most monumental of the three facades. Dedicated to the Celestial Glory of Jesus, it will represent the road to God: Death, Final Judgment, and Glory, with Hell awaiting those who deviate from God’s will. The portico will have seven large columns dedicated to spiritual gifts. At their bases will be representations of the Seven Deadly Sins, and at their tops, The Seven Heavenly Virtues. Behind these will be the spires for the remaining four apostles. The completion of this façade will require the demolition of the whole block of buildings across the Carrer de Mallorca. To reach the Glory Portico, a large staircase will lead over the underground passage built over Carrer de Mallorca with the decoration representing Hell and vice.

2006 — Work concentrates on the crossing and supporting structure for the main tower of Jesus Christ, as well as the southern enclosure of the central nave, i.e., the interior side of the Glory façade.

2008 — Some renowned Catalan architects call for halting construction to respect Gaudí’s original designs, which although not exhaustive and partially destroyed, have been partially reconstructed in recent years.

2010 — Construction passes the midpoint spurred on by advances in technology such as computer aided design and computerised numerical control (CNC).

2010 November — Pope Benedict XVI consecrates and proclaims Sagrada Familia a minor basilica.

2012 — Barcelona-born Jordi Fauli becomes chief architect.

2015 — Chief architect Jordi Fauli announces in October 2015 that construction is 70 percent complete and has entered its final phase: raising the six tallest spires, those representing the Virgin Mary, the four Evangelists and, tallest of all, Jesus Christ. Gaudí’s original design called for a total of eighteen spires, to represent, in addition to the noted six spires, the Twelve Apostles. As of 2010, eight of the ‘Apostle’ spires have been built: at the Nativity façade—Matthias, Saint Barnabas, Jude, and Simon the Zealot; at the Passion façade — James, Thomas, Philip, and Bartholomew. As to the height of the six tallest spires: According to the 2005 “Works Report” of the project’s official website, drawings signed by Gaudí and recently found in the Municipal Archives indicate the spire of the Virgin will be shorter than the spires of the Evangelists. The Evangelists’ spires will be surmounted by sculptures of their traditional symbols: Saint Matthew—a winged man, Saint Mark—a winged lion, Saint Luke—a winged bull, and Saint John—an eagle. The central spire of Jesus Christ, surmounted by a giant cross, will reach 170-metres/560 ft., one metre less than the height of Montjuïc, Gaudí believing that his creation should not surpass God’s. When the spires are completed, Sagrada Família will be the tallest building in Barcelona, and the tallest church in the world.

2018 — Current projections are for completion of the church’s structure and the spires by 2026, the centenary of Gaudí’s death. Decorative elements should be completed by 2030 or 2032.

QUOTATIONS ABOUT SAGRADA FAMILIA

Rainer Zerbst, art critic: “It is probably impossible to find a church building anything like it in the entire history of art.”

Paul Goldberger, architectural journalist: “The most extraordinary personal interpretation of Gothic architecture since the Middle Ages.”

Fodor: Its towers and cranes are visible from all over Barcelona and it is the one must-see sight on every itinerary.

Fodor: At first glance, the entire church looks like the work of a fevered imagination, but every detail of every spire, tower and column has its own precise religious symbolism, which is why the Sagrada Familia has been called a ‘catechism in stone’.

Fodor: It is something of an irony that a building widely perceived as a triumph of Modernisme, with all its extravagance, should have been conceived as a way of atoning for the sins of the modern city.

George Orwell, English novelist in his account of the Spanish Civil War, Homage to Catalonia (1938): “I think the anarchists showed bad taste in not blowing it up when they had the chance.”

Robert Hughes, art critic regarding the Passion façade: “…the most blatant mass of half-digested moderniste clichés to be plunked on a notable building within living memory.”

I have not yet found information on the windows: who designed them, who manufactured them, when they were installed, and what work remains. Presumably remaining work includes the windows for the Glory Façade. I believe it was our guide who told us that the cool/warm division—cool blues and greens on the east Nativity side, and warm yellows, oranges, and reds on the western Passion side of the nave—follows Gaudi’s plan. In another break from tradition the window designs are abstract, not illustrations of the scriptures, further reinforcing the ‘catechism in stone’ description. In Antoni Gaudi, The Complete Buildings, Rainer Zerbst says the following about Gaudi’s use of colour:

“Colours were also used symbolically. Gaudi intended, for example to use green for the Portal of Hope. With its rather more joyful themes, the eastern façade as a whole was meant to be bright and colourful, whereas Gaudi wanted to have the façade of Suffering in sombre colours. He certainly did not want to leave the stone in its natural hues. Gaudi hated monotony of colour—he found it unnatural. Nature, he frequently preached, never showed itself monochromatically or in complete uniformity of colour, for it always contained a more or less clear contrast of colours. For Gaudi, who in the course of his life felt increasingly influenced by Mother Nature as a teacher, this meant the architect was called upon to give all the elements of architecture at least some touch of colour.” p203

Perhaps taking photos was distracting, but I am so glad I did. They show some of the effects of the stained glass windows on the interior colours, and on the quality of the interior light. And they have helped me better see all that I couldn’t take in at the time. Despite the clarity of the modern decorative elements, and the simplicity of their pure geometric form, there is a lot going on, a lot to take in. Visual information is layered on all the surfaces: overhead, underfoot, at corners, around corners, at the base and at the tops of the interior tree-like columns. But when you are able to organize it, the patterning is breathtaking. Moving through the space is like being inside a giant kaleidoscope turned by your own ambulation.

When the structure is completed providing entry through the Glory facade at the base of the nave rather than through the transept facades as, by necessity, has occurred since the work began, much of this ‘pattern construction problem’ will likely be resolved. Visitors and worshippers will recognize the underlying traditional layout, and then be freed up to focus on the form and functionality of the columns, and the other decorative features.

Sagrada Familia is the most unique, and inspiring and, dare I say it, beautiful space I have ever been in. It cannot be oversold. Any guidebook on Barcelona that short shrifts it should not be regarded as a reliable resource. I hope to see it again soon and spend more time both inside and out. And I will add it to my list of things to see at night in Barcelona. I also hope to visit it once completed. Surely it will be the most awe-inspiring church in all of modern Christendom. ‘Bah humbug’ to George Orwell and Robert Hughes.

8. Lunch on Las Ramblas and a walk along the Beach

… Then we had the remainder of the day at our leisure in Barcelona. We needed lunch, so, having decided to make the Barcelona beach—Platja de Barceloneta— our destination, we walked down La Rambla looking for an outdoor restaurant with a light tapas-type lunch menu. I have no record of the name of our choice, and reviewing the listings for ‘Outdoor Seating Restaurants in La Rambla on Tripadvisor hasn’t prompted my memory. But the reviews I have seen confirm that our experience wasn’t unique: expensive, terrible service, and horrible food. We should have known better but we were hungry, needed to sit, and wanted to bust out of our timid ‘eat in our hotel’ approach. These places look like classic ‘tourist traps’ and they are.

We walked down to the Mirador Colom (Tower of Christopher Columbus at the base of La Rambla), along the Moll Boschi Alsina, over the Rambla del Mar, a floating footbridge that “extends the Rambla as far as the Maremagnum area,” all around the Maremagnum Terminal, and then, by hugging the water we somehow made our way to the paved sidewalk beside the beach that eventually steps up to run parallel but above it.

From the footbridge we saw the floating sculpture officially called ‘The Stargazer’. Online information is as follows:

“A few metres from the Rambla del Mar walkway, two pristine white figures float silently in the waters of Barcelona harbour. The 3.55m polyester and fibreglass sculptures, their gaze turned up to the heavens, were designed by Robert Llimós and built by local shipbuilder Marina 92. [Robert Llimós is a Catalan painter and sculptor born in Barcelona in 1943.] The Stargazer (Catalan: Miraesteles) statues are 2 of a series of sketches, paintings and statues inspired by the poem El Saltamartí (grasshopper) by Joan Brossa. The poem uses the image of a person looking upwards at the night sky as a symbolic representation of humanity. The first aquatic version of Stargazer was installed in Sitges [town about 35 kilometres southwest of Barcelona] in 2007 where it was seen by the director of the Barcelona boat show who was so taken by the statue that he commissioned one for the Port Vell harbour. In 2010 the Barcelona Foundation for Ocean Sailing (FNOB) presented 2 statues to the port to commemorate the New York – Barcelona transoceanic sailing record.”

The Maremagnum Terminal berths super yachts (over 40 meters/130 feet) and possibly even mega yachts complete with helicopter pads, forests of radar equipment, multiple decks, most flying ensigns and showing registration in George Town, the capital of the Cayman Islands.

Guidebooks say “the people of Barcelona enjoy the sun and the sea of their beaches throughout the year” and this day was no exception. The weather was lovely throughout the day—not necessarily ‘bake on the beach’ lovely, but there were enough sunbathers to make it a fun people-watching place.

We kept our eye on Frank Gehry’s golden fish sculpture, El Peix, another un-missable landmark built for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. It serves as a canopy for the casino and restaurants linking the luxurious Hotel Arts to the seafront. El Peix is just west of the Port Olimpic. Online information reads as follows:

This giant goldfish, … one of the symbols of post-Olympic Barcelona … looks as if it is bobbing along on the waters of the Mediterranean. … In 1992, the pristine Olympic Barcelona was transforming its seafront. A new Olympic Marina was taking shape, presided over by its twin towers. On one side stood the Mapfre Tower; on the other … the Hotel Arts. Frank Gehry placed his fish sculpture at the foot of the hotel. The animal is 56 metres long and 35 metres high and seems to be longing to jump into the blue waters of the Mediterranean. The sculpture was made from intertwining gilded stainless steel strips supported by a metal structure, its gentle, subtle form marked by its intense gold colour. The interplay between the rays of the sun and skin creates the impression of scales, depending on the intensity of the light, and accentuates the organic form.

El Peix was our endpoint and we were done. We taxied back to our hotel to relax before dinner out. Next time: Staying closer to or on this beach would be tempting, including finding some great seaside restaurants (but not tourist traps!)

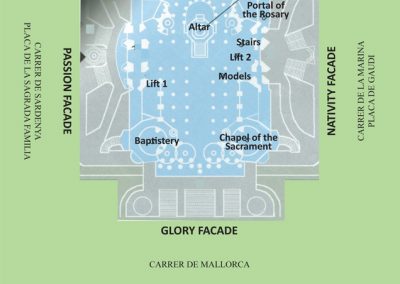

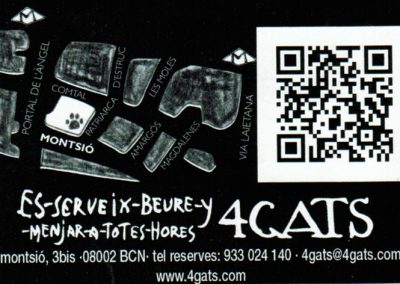

9. Dinner at 4Cats

Els Quatre Gats means “The Four Cats,” which is derived from a Catalan expression meaning “only a few people.” The phrase is usually used to describe people who are a bit strange, or perceived as outsiders. 4Cats opened on June 12, 1897 in the famous Casa Martí, and served as a hostel, bar, and cabaret. The bar closed due to financial difficulties in June 1903, but 86 years later was reopened and eventually restored to its original condition in 1989.

Romeu, the founder of the original 4Cats had worked at a French café called Le Chat Noir. Three of his friends, Ramon Casas, Santiago Rusiñol, and Miguel Utrillo, all major modernist Spanish artists of the time provided him with financial support. Casas even painted for the interior of the café his now famous painting, Ramon Casas and Pere Romeu on a Tandem depicting them riding a tandem bicycle. A simple outline in the background traces the Barcelona skyline. An inscription on the painting reads, “To ride a bike, you can’t go with your back straight,” expressing the founders belief that progress and making something great requires breaking with tradition. The painting is in the National Art Museum of Catalonia, a copy hangs in the café, and the image is on the current business card.

In addition to offering good food and drink, the founders wanted 4Cats to provide “food of the spirit.” By hosting performances, concerts, art exhibitions, and literary gatherings, it attracted important modernist and bohemian artists, architects —Gaudí, and sculptors. In 1899, Pablo Picasso, then 17, began frequenting 4Cats and held his first solo exhibition in the main room. Our introduction to 4Cats was thanks to the Winer family’s dinner invitation. We enjoyed the delicious food, great service and ambience, and of course their great company. And it was only steps away from our hotel. Thank you Nathan, Marcia, and Ellen for your generosity of spirit. It was the perfect top-off to an unforgettable day.

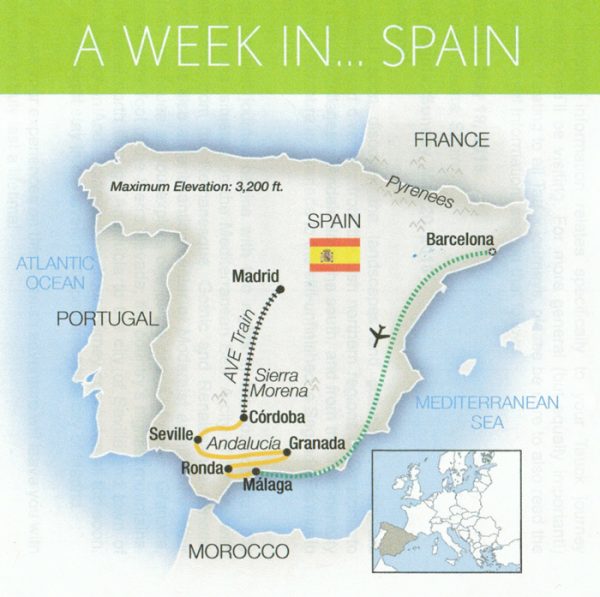

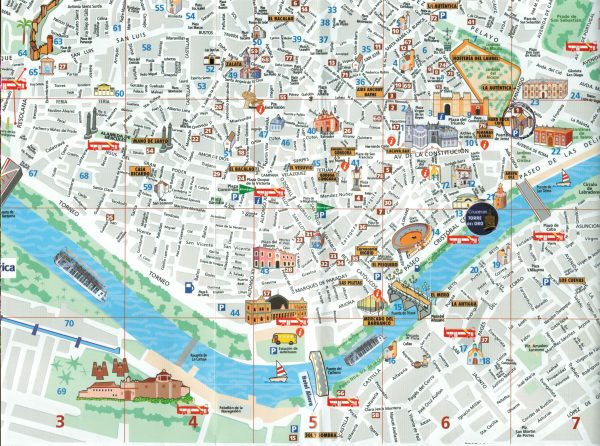

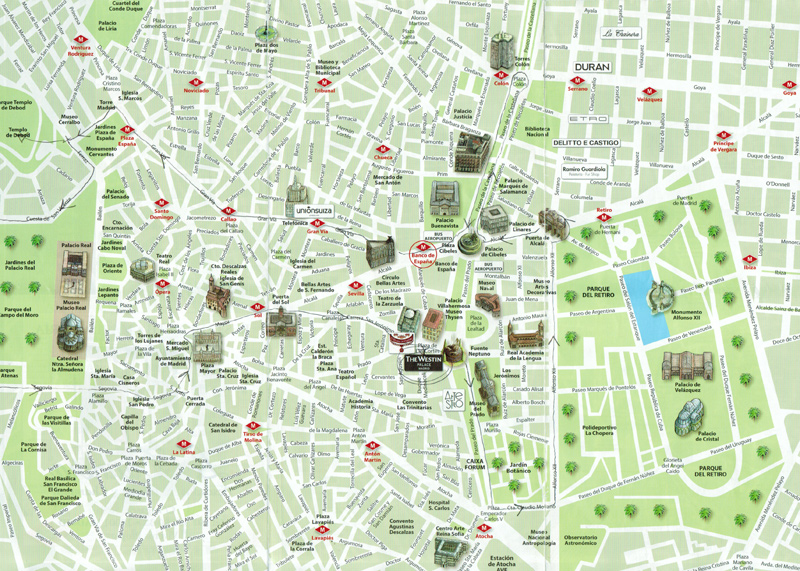

DAY 4: Tues May 22, 2018 - Fly to Malaga, Bus to Ronda, Bus to Granada

1. Flight to Malaga One of the best features of shipboard cruising is unpacking your suitcase only once. Shipboard cruising is for turtles like me. Land cruising is for life-long learners, those who like to figure out a different plumbing system every night, those who adapt readily, and like to strategize—smart jackrabbits! If your land cruise calls for leaving early the next morning, for instance, you must have your suitcase packed and ready for pick-up the night before. So you have to plan the clothing and toiletries you will need to hold back for your day bag. You get used to this, but, fundamentally, turtles don’t aspire to becoming jackrabbits. … But somehow we managed. Day 4 and we were up early dressed as we had been the night before, with our teeth brushed before breakfast (!) in time for our bus to the airport and from there, in short order, our flight to Malaga. Land cruising with Tauck has to be the best such experience on offer. On an early call day, you organize getting your teeth brushed; they attend to every other detail. Malaga is 770 km by air/478 nautical miles from Barcelona. Every aspect of our 1.5-hour flight went so smoothly I have almost no memory of the experience.

One of the best features of shipboard cruising is unpacking your suitcase only once. Shipboard cruising is for turtles like me. Land cruising is for life-long learners, those who like to figure out a different plumbing system every night, those who adapt readily, and like to strategize—smart jackrabbits! If your land cruise calls for leaving early the next morning, for instance, you must have your suitcase packed and ready for pick-up the night before. So you have to plan the clothing and toiletries you will need to hold back for your day bag. You get used to this, but, fundamentally, turtles don’t aspire to becoming jackrabbits. … But somehow we managed. Day 4 and we were up early dressed as we had been the night before, with our teeth brushed before breakfast (!) in time for our bus to the airport and from there, in short order, our flight to Malaga. Land cruising with Tauck has to be the best such experience on offer. On an early call day, you organize getting your teeth brushed; they attend to every other detail. Malaga is 770 km by air/478 nautical miles from Barcelona. Every aspect of our 1.5-hour flight went so smoothly I have almost no memory of the experience.

Wikipedia says Málaga is the second-most populous city (population 570,000 in 2015) in Andalusia, Spain, and the sixth largest municipality in Spain. “The southernmost large city in Europe, it lies on the Costa del Sol (Coast of the Sun) of the Mediterranean, about 100 km (62 mi) east of the Strait of Gibraltar, and about 130 km (80 mi) north of Africa.”

Founded by the Phoenicians in 770 BC, it was subsequently ruled by ancient Carthage, then the Roman Republic, followed by the Roman Empire, followed by the Visigoths, followed by the Moors. In 1487, the Crown of Castille gained control after the Reconquista and has more or less remained in charge ever since. In 2016, it was a candidate for European Capital of Culture. It was the birthplace of Pablo Picasso and Antonio Banderas who recently fulfilled his life-long ambition as an actor to portray Picasso. Tourism, construction, and technology services are key business sectors. An estimated 6 million tourists visit the city each year to soak up the sun on the beaches, and Malaga’s rich and diverse art and culture. But, alas, we were just passing through. We got on our tour bus, pronto, and took off for Ronda.

2. Bus to Ronda

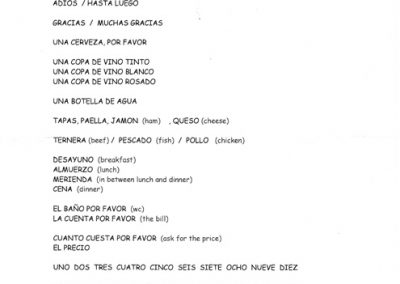

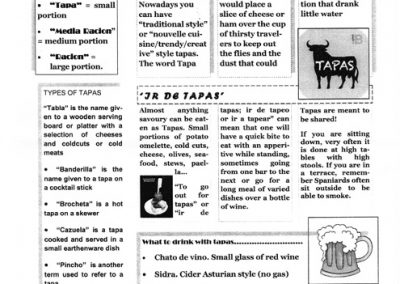

I must have slept at least part of the way — buses rock gently! — because, once again, I have only vague memories of this trip. One moment we were rounding a ramp to the main highway that passed by a huge Costco store, the next we stopped briefly for a bathroom break at a roadside tourist shop, … and then we rolled into Ronda around lunchtime. I seem to recall carefully tended countryside, green and prosperous looking all along the way. Alicia had gifts for us after our stop at the tourist shop—fans for the ladies—and she provided us with information on the origin and language of the fan. She also talked about tapas and Spanish wine, and gave us information sheets on these topics. And we took a brief language lesson, also backed up by an information sheet.

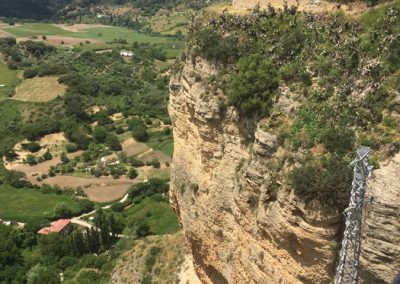

Ronda is perched on a high rock outcrop surrounded by the limestone peaks of the nearby Sierras. Bisected by the El Tajo gorge, the two parts of Ronda are connected by three bridges, the most famous of which is the ‘Puente Nuevo’ or New Bridge. Ronda is a popular tourist destination with its stunning views, “beguiling labyrinth of streets, impressive palaces, mansions and churches and convents,” and “thousands of years of history and culture.” It has played a significant role in the long tradition of bull fighting in Spain housing a famous bullring and spawning dynasties of famous bullfighters. Of Ronda’s overall cultural influence Wikipedia writes: “American artists Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles spent many summers in Ronda as part-time residents of Ronda’s old-town quarter called La Ciudad. Both wrote about Ronda’s beauty and famous bullfighting traditions. Their collective accounts have contributed to Ronda’s popularity over time. [After Orson Welles died in 1985, his ashes were buried [near Ronda] in a well on the rural property of his friend, retired bullfighter Antonio Ordoñez.] … In the first decades of the 20th century, the famous German poet Rainer Maria Rilke spent extended periods in Ronda, where he kept a permanent room at the Hotel Reina Victoria (built in 1906); his room remains to this day as he left it, a mini-museum of Rilkeana. According to the hotel’s publicity, Rilke wrote, … “I have sought everywhere the city of my dreams, and I have finally found it in Ronda” and “Nothing is more startling in Spain than this wild and mountainous city.” Ronda was also acknowledged in 19th century literature by George Eliot in her last novel, Daniel Deronda, published in 1876, about a man searching for his origins, his name indicating his ancestors’ connection with Ronda prior to the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492.

Some facts:

- Ronda (population about 35,000) is located about 100 km (62 mi) west of Málaga

- At about 750 m (2,460 ft) above mean sea level, it is perched on top of the 100-plus-meter-deep El Tajo canyon through which flows the Guadalevín River.

- The Spanish fir (Abies pinsapo) covers the surrounding mountains.

Some history:

- Neolithic Age — remains of prehistoric settlements dating to this time period have been uncovered around Ronda including the rock paintings of Cueva de la Pileta.

Cueva de la Pileta rock painting

- 6th Century BC — first settled by early Celts, who called it Arunda

- …then settled by the Phoenicians

- Second Punic War — Romans founded the current Ronda as a fortified post in the Second Punic War, by Scipio Africanus. Ronda received the title of city at the time of Julius Caesar.

- 5th Century AD — conquered by the Suebi or Germanic tribes.

- 713 — part of the Visigoth realm until 713, when it fell to the Berbers.

- After the disintegration of the caliphate of Córdoba, Ronda became the capital of a small kingdom ruled by the Berber Banu Ifran, the Taifa of Ronda, the period during which Ronda gained most of its Islamic architectural heritage.

- 1065 — conquered by the Taifa of Seville led by Abbad II al-Mu’tadid.

- 1485 — after a brief siege the Marquis of Cádiz ended the Islamic domination of Ronda. Subsequently, most of the city’s old edifices were renewed or adapted to Christian roles, while numerous others were built in newly created quarters such as Mercadillo and San Francisco.

- early 19th century — the Napoleonic invasion and the subsequent Peninsular War reduced the population from 15,600 to 5,000 in three years. Ronda and its surrounds became the base for guerrilla warriors, then numerous bandits, whose deeds inspired artists such as Washington Irving, Prosper Mérimée, and Gustave Doré.

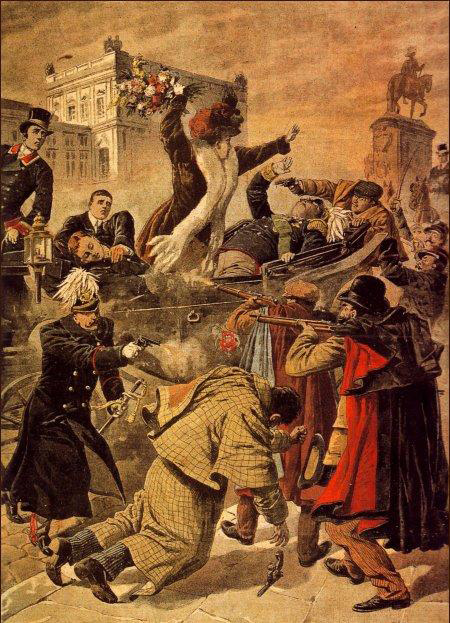

- Spanish Civil War — heavily affected Ronda causing emigration and depopulation. (The scene in chapter 10 of Hemingway’s, For Whom the Bell Tolls, describing the 1936 execution of Fascist sympathisers in a fictional village who are thrown off a cliff is considered to be based on events that occurred in Ronda.)

The three famed bridges spanning the El Tajo canyon:

1. Puente Romano —‘Roman Bridge’ also known as the Puente San Miguel

2. Puente Viejo —‘Old Bridge’ also known as the Puente Árabe or ‘Arab Bridge’

3. Puente Nuevo —‘New Bridge’

- 1735 — The first attempt to span the gorge at this height was a single arch bridge designed by the architects Jose Garcia and Juan Camacho. Quickly and poorly built, this bridge collapsed in 1741 killing 50 people.

- 1759 — Beginning of construction of the bridge that stands today, the tallest of the bridges towering 120 m (390 ft) above the canyon floor

- José Martin de Aldehuela was the architect and he also designed the Plaza de Toros de Ronda — died in Málaga in 1802.

- Juan Antonio Díaz Machuca was the chief builder.

- 1793 — Bridge completed. The chamber above the central arch was used for a variety of purposes, including as a prison. The chamber is entered through a square building once the guardhouse. It now contains an exhibition describing the bridge’s history and construction.

- 1936-1939 — During the civil war both sides are alleged to have used the prison as a torture chamber for captured opponents.

Poster for the Corrida Goyesca by Villalta

3. Lunch at Parador Ronda

Our first taste of Ronda was a sit-down, multi-course lunch at the Especia del Parador de Ronda, a medium-sized dining room with lots of ‘French-door-like’ windows providing access to the wrap around balcony, which in turn provides the aforementioned stunning views towards the mountains and the farmlands in the deep valley below. This Parador is in Ronda’s old Town Hall, which is perched cliff-top overlooking the gorge on one side, and the valley and mountains on the other. I did not keep a copy of our menu—pre-set offering a main course meat or fish option. The meal was delicious, and we dined with the ‘Exotic Omas, a big treat as well! We even allowed ourselves wine with lunch, an indulgence I try to avoid. Dinner without wine is another matter.

Note: Parador Hotels

(Paraphrased From Wikipedia) “Paradores de Turismo de España is a chain of Spanish luxury hotels although the English translation of the Spanish word parador is hostel, which doesn’t connote luxury. Nevertheless the company was founded by Alfonso XIII to promote tourism in Spain and it seems to have been a visionary idea successfully implemented. The first hotel opened in 1928 in Gredos (Ávila). The hotels are often located in adapted castles, palaces, fortresses, convents, monasteries and other historic buildings. … The Hostal de los Reyes Catolicos in Santiago de Compostela is considered to be one of the oldest continuously operating hotels in the world, and one of the finest Spanish paradors.” Paradors were traditionally located in areas where there was minimal competition with the private sector, i.e., in smaller medieval towns and villages. Today, with the explosion of tourism in Spain, in addition to their prime locations, Parador Hotels are renowned for their high quality service and relatively reasonable pricing.

4. Guided Tour of Ronda

After lunch we took photos from the balcony and then connected with our “yellow” group to tour Ronda with a knowledgeable guide with a serious demeanor, but who lacked shepherding skills, and who’s heavily accented English was difficult for me to follow. He did have one ‘joke’ for us though, something along the lines of: There should be a rule in Ronda that unless you know for certain it isn’t true, you should have to declare of your establishment, ‘Ernest Hemingway did not dine here.’ Then, he said, every other sign about Hemingway could be disappeared. For a guy in the tour guiding business his was a witty and realistic take on what most tourists are thinking anyway.

Note: Hearing Issues

In my experience, hearing aides and the microphone in the portable device that connect you to your guide do not combine well. My hearing aides would turn off when the device had been activated for a while. Then I would have to disconnect everything and reset my hearing aides, although they often wouldn’t function properly again for a couple of hours. Good thing I had an extra set with me, my audiologist having urged me to test a new brand during my trip.

Our tour began at the Town Hall, crossed the Puente Nuevo, veered left to the square providing a lookout down to the Guadalevín River, and then took us back to the main street passing by the Palacio De Congresos Y Exposiciones.

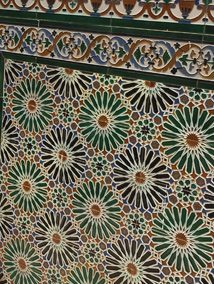

Our next stop in the heart of old Ronda on Calle Tenorio was the House of Don Bosco (Casa de Don Bosco) built in a modernist style at the beginning of the 20th century. Originally belonging to one of Ronda’s wealthy families, it was donated to the Salesian Order, declared a historic monument in 1931, and is currently used as a retreat and retirement home for priests. Public access is limited to the ground floor and the gardens. The interior is noteworthy for the tile work on the walls and floors; the exterior for the view of the canyon and the Puente Nuevo, and the Arabic style mosaics decorating the walls, benches, walkways, and central pond with spouting frogs. Don Juan Bosco (also known as St. John Bosco) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest, educator, and writer of the 19th century (1815–1888) who dedicated his life to the betterment and education of street children, juvenile delinquents, and other disadvantaged youth. His teaching methods based on love rather than punishment, became known as the Salesian Preventive System.

From here we walked by the Museo Ronda (but didn’t go inside), through narrow laneways to the square beside Saint Mary’s Church (Iglesia de Santa Maria la Mayor) dating from the 15th Century and converted from a mosque into a church by Fernando ‘El Catalico’. We walked the pathways through the Plaza Duquesa de Parcent, where we turned to circle back to the Puente Neuvo, passing Lara’s Museum (Museo Tematico Lara) located in the House Palace of the Counts of the Conquest, dating from the 18th Century, and housing “the most important private collection in Spain.” (…but we didn’t go inside.)

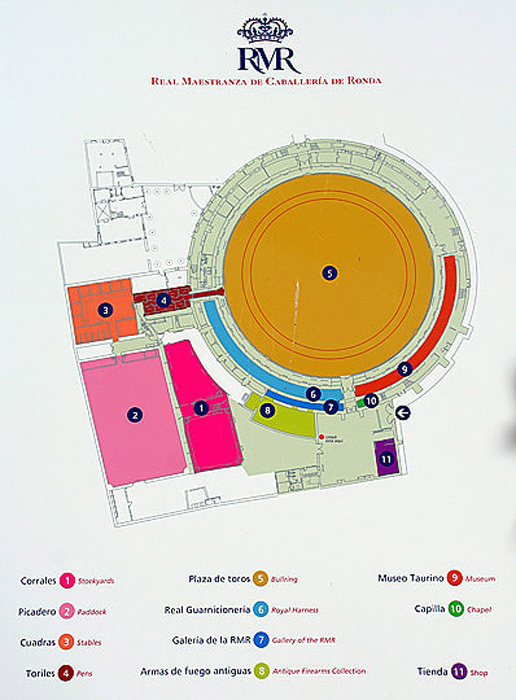

We re-grouped in front of the Town Hall, then set off for our final destination: Ronda’s famous Plaza de Toros and beside it, the Museo Taurino.

Notes: Ronda and Bullfighting

The history of bullfighting in Spain has many connections with Ronda and is closely linked to the history of the Maestranza of Ronda. The term ‘maestranza’, not used until the mid-seventeenth century in Andalusia (a derivation of the word “master or maestro”) was given to anyone involved in teaching the art of la jineta, an Arabo-Andalusian style of horsemanship. On September 6, 1572, Philip II, decreed that the knights and other leading gentlemen within the cities, towns and villages of his Kingdom should establish Brotherhoods, Companies or Orders dedicated to preparing for war by participating in tournaments, lance jousting, shot-put contests, gymnastic rings, and bull spearing, a popular spectator sport but also a component of equestrian training. In Ronda, Philip II’s decree was read at a council meeting on September 22, 1572. The Chief Magistrate and the attending knights representing the city, according to custom, removed their hats, took the King’s letter in their hands, kissed it, and placed it on their heads as a sign of reverence. Accordingly, in 1573 in Ronda, The Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit, later to become known as the Maestranza was established choosing for their patron saint, Our Lady of Grace. In 1575, Philip II instructed the Maestranza of Ronda to ensure that the knights did their very best to breed “good horses for the guard and defence of the Kingdom.” At this time The Maestranza was “an educational institution, an authentic school providing military instruction, whose catechism was encapsulated in the graceful art of horsemanship and spear fencing, which were proudly displayed during public feast days occurring on designated days, whose exercises and designation came to be their first and only ordinances.”